The Lindisfarne Saga - ZigZag 50

Three years ago it seemed like the end of an era.

Alan Hull was to be found in his once favourite haunt, the Nellie Dean, soon after opening time, and was well on the path to honouring that self-created tradition of drinking into oblivion. A battered old suitcase stood alongside, that would sometime in the evening be accompanying its owner back to Newcastle.

It was a meeting of some coincidence. For only hours earlier I had been commissioned to write The Lindisfarne Story, and whilst always aware of, and frequently involved in all the stations on the way as Lindisfarne progressed >from support band at the Marquee to national headliners, it must have been two years now since I sat down and talked to Alan Hull in any set of circumstances.

But now he was calmly accepting the fissure that had finally terminated the name of Lindisfarne with a sort of dogged inevitability and I swear he had the words "Geordies are a crazy bunch of bastards2 etched on his lips, where "crazy2 would once have read "canny".

Back on his own again, Alan Hull's future suddenly looks far more decisive. There is a new solo album

Squire - a sequel to that fine Tom Pickard TV play in which Alan fully justified his acting debut.

Back on his own again, Alan Hull's future suddenly looks far more decisive. There is a new solo album

Squire - a sequel to that fine Tom Pickard TV play in which Alan fully justified his acting debut.

"They call me the squire," bawled out Hully, in earshot of all the Nellie regulars, using the conjunctive first line of the song which linked each dream sequence of the film in true Lennonesque fashion. Then, in answer to an imaginary encore, he sang a new song called 'One More Bottle Of Wine', a

familiar 2oth century music hall theme written by the drunk for the drunk and designed to be sung slightly off key. As far as I know he sang the entire song.

In April Alan Hull will take the stage afront a twenty piece orchestra and there will be a further perm of Geordies - the names of Pete Kirtley and Colin Gibson were mentioned, and of course there will be a couple of Lindisfellows.

Alan Hull is pinning high hopes on his new solo album and in all truth his credibility as a songwriter will surely be judged on his next performance. Thankfully he is no longer pulling old items out of the vaults but has 100 per cent new songs for sale.

By eight o' clock on that evening James Alan Hull was sufficiently rummed and pepped to undertake his 300 mile journey into the future. ZigZag meantime, turns back the pages. I still derive a certain amount of pride from being the first writer to predict Lindisfarne's success.

It was September 1970 and Tony Stratton-Smith will doubtless remember better than I the band who Lindisfarne had been brought in to support. But the two of us took our place in the painfully sparse arena, and perhaps because my ears had always supported the tenet that song construction, melodically and rhythmically, was all important, I became sold on the band instantly. They had a nice fat acoustic sound which was so erratic and carefree it immediately took me back to my old worn Sonny Terry/Woody Guthrie/Cisco Houston combination records. Why, they even played an old Guthrie song, 'Jackhammer Blues'.

A few weeks later, still struggling to make an impact, Lindisfarne were back at the Marquee and I recall unhesitatingly singing along with half the songs as though I'd heard them twenty times.

It was at the Marquee some months earlier that Alan Hull, soloist, had played the Wednesday folk nights (organised, I recall, by Judith Piepe, who has systematically pinpointed the best talents to emerge on the London folk scene over ten years).

It was at the Marquee that Tony Stratton-Smith decided to sign the band to Charisma, at a pub called the George in WC2 that I first interviewed the band and at the old Charisma offices in Brewer Street that I was played the acetate of an album called Nicely Out Of Tune which mushroomed eleven potential hit singles.

By November 1970 I was absolutely convinced of Lindisfarne's pedigree. They were still coming down from Newcastle, roadies sleeping in the truck, the band begging drinks in La Chasse Club . . . but they secretly knew that they were going to be the catalyst in goading public taste back to good songs, delivered in the same raw patois that had distinguished the early Beatles' Liverpool success.

"We're a songwriters' band and we've got to wait for the audiences to catch up with us now," exclaimed a confident Alan Hull. "We're nicely out of tune with what other people are doing - that's why we chose it for the album title."

The story goes that Charisma decided the single on the flip of a coin . . . although it could easily have been 'Turn A Deaf Ear', 'Lady Eleanor' which was later to become a huge hit, or 'We Can Swing Together' which ironically Alan had already put out as a single whilst a folk singer with Transatlantic. It was in May 1970 that Alan had joined forces with Newcastle blues/folk band Brethren, and in so doing ended any chances he might have had of forming a band with fellow Geordies Jon Turnbull and Graham Bell. Brethren had turned up to play an acoustic guest spot at Alan's Whitley Bay club, The Rex, and he was knocked out with what he heard - particularly Ray Jackson's harmonica work. "They wanted to back me on some tapes I was doing and this led to us all doing a gig together, which was terrible. But we gave it another try and it was fantastic, so I joined - and as it turned out we had exactly the same ideas in mind anyway," said Alan soon afterwards.

By June of 1971 Lindisfarne were headlining a concert at the Royal Festival Hall promoted by Jo Lustig, who had also long been singing the group's praises. Unicorn and Gillian McPherson were also o the bill. This was the first milestone. Word of the band's success had spread like wildfire and that summer Bob Johnston, producer of albums by Dylan, Cohen and Cash, flew to London to produce Fog On The Tyne. It was a decision which I'd always felt a little doubtful for although John Anthony's name didn't quite carry the same prestige as Johnston's he did a great job on that first album and even little producers' tricks like the scratched effect on 'Down' somehow seemed to enhance the overall chaos.

If there was one thing Lindisfarne didn't need at this point, it was sophistication, and when at the end of the Fog On The Tyne sessions a press hearing was called, the worst fears were confirmed. Johnston sat back behind the console like a modern day Henry VIII rolling joints. The summer had given birth to another crop of fine songs and Alan was quite happy to plunder the vaults at Newcastle's Impulse Studios whilst Rod Clements plagiarised Dylan and came up with 'Train In G Major', a knock off from 'It Takes A Lot To Laugh', which was to become a great stage number.

But Rod also came up with the hugely successful 'Meet Me On The

Corner' and on a first side top heavy with good songs there was also 'Alright On The Night' (another hit), 'Together Forever' (like 'Turn A Deaf Ear' by Kirkcaldy folk singer Rab Noakes who was later to tour with the band) and also 'January Song'.

One of the problems Lindisfarne encountered in the second half of 1971 was living up to their reputation of being carefree rough diamonds who came onstage drunk and were running a promo campaign for the Magpies and Newcastle Brown Ale. The image had been promoted largely by jovial Ray Jackson, his penchant for playing good old music hall medleys on harmonica and the fact that he had a far thicker patois than any of the other band members. This is not aimed as a criticism for it gave the group a solid identity so that even the cursory listener could link the band inextricably with Newcastle. Paradoxically this later imposed restrictions which were to bring about their downfall.

'Alright On The Night' (another hit), 'Together Forever' (like 'Turn A Deaf Ear' by Kirkcaldy folk singer Rab Noakes who was later to tour with the band) and also 'January Song'.

One of the problems Lindisfarne encountered in the second half of 1971 was living up to their reputation of being carefree rough diamonds who came onstage drunk and were running a promo campaign for the Magpies and Newcastle Brown Ale. The image had been promoted largely by jovial Ray Jackson, his penchant for playing good old music hall medleys on harmonica and the fact that he had a far thicker patois than any of the other band members. This is not aimed as a criticism for it gave the group a solid identity so that even the cursory listener could link the band inextricably with Newcastle. Paradoxically this later imposed restrictions which were to bring about their downfall.

On a Saturday in December 1971, Lindisfarne went home for a concert at Newcastle's City Hall, and if the scenes were heartwarming for the band they were stunning for us outsiders who were there to report on the bond that linked several thousand Geordies with the five prodigals who had come home for Christmas. All the telltale trimmings - music hall decor, genuine Newcastle Brown ale promotion, hippies with sleeping bags who had trekked miles.Stealers Wheel, Rab Noakes and Roger Ruskin Spear, I recall, created a terrific build up for the band and I swear there was a prevailing hysteria. All Lindisfarne could have seen gazing out into the vast auditorium was the occasional body teetering dangerously over the edge of the balcony. It's a wonder no one was killed that night. Jacka played on oblivious - into the medleys, even 'Pretty Thing' and 'Not Fade Away' with a fond hark back to Brethren. Before the end of the night Lindisfarne had been augmented by Charlie Harcourt and Kenny Craddock who were later to team up with Alan and Jacka in Lindisfarne Mark II.

In March 1972 Lindisfarne took off for the States having firmly consolidated their position in Britain and confident of similar success in the US. They had signed a record deal with Elektra which, on the face of things, looked to be a good label for the band because whilst the glorious days of Elektra definitely belonged to the middle and late sixties, they were showing signs of a resurgence. But it seems to me that they never quite got to grips with how they should promote this ragged beast called Lindisfarne.Only the legendary Billy James seemed to realise that harmony could best be created by sharing a few ales at a rare Los Angeles pub called the Mucky Duck, but it often seemed as though he was fighting a lone battle; while Elektra execs scratched their heads, American punters who had been weaned on professionalism and perfection, two tiresome ingredients that Lindisfarne were seldom known to inject into their act, were wondering what all the fuss was about.

I'd always enjoyed interviewing Alan Hull and was aware of a fascinating past that had never been probed. The visible iceberg had been sapped dry but the murky past had not and in May 1972 he gave me a fascinating interview

(Sounds Talk In 27/5/72) which remains one of my favourites to this day. Somehow he managed to put to put his songs in perspective in the light of his philosophy, the books he had read, his days as a mental hospital nurse, his changing ideology, his preoccupation with madness and the resultant songs that he never dared sing in public. So many of his best songs had sprung from this rather intense period and there and there was so much hidden depth in that year of Our Lord one thousand nine hundred and seventy two, he must have been rather bemused at the accolades that were suddenly being heaped upon him. For the truth of the matter was that as a songwriter, Alan Hull was running dry. He explained: "The only thing that's troubling me now is the songs - you know, the material that's coming out now because it's only reflecting something that isn't really real. Rod's just written a song that's the best thing I've ever heard, it's the song I've been trying to write this past two years since the whole thing with Lindisfarne happened. I think it's going to be the best song that Lindisfarne will ever do."

['Don't Ask Me' on Dingly Dell.]

was so much hidden depth in that year of Our Lord one thousand nine hundred and seventy two, he must have been rather bemused at the accolades that were suddenly being heaped upon him. For the truth of the matter was that as a songwriter, Alan Hull was running dry. He explained: "The only thing that's troubling me now is the songs - you know, the material that's coming out now because it's only reflecting something that isn't really real. Rod's just written a song that's the best thing I've ever heard, it's the song I've been trying to write this past two years since the whole thing with Lindisfarne happened. I think it's going to be the best song that Lindisfarne will ever do."

['Don't Ask Me' on Dingly Dell.]

Alan confessed that all his worries were centred on his own writing. "I'm still getting the tunes together and the chord changes but . . . the only things I want to say are what Rod's just said, and the only thing apart from

that is very religious and I don't think people wanna hear that. The only thing I wanna write about is getting drunk."

Alan has always walked a tightrope with his lyric writing because, like Lennon's lyrics, they were couched ridiculously simply. Simplistic and blunt - Randy Newman is another genius at that style of writing but when it's not happening . . . not really flowing, then it's all too easy to allow a trite lyric to slip in vicariously. This is what I believe happened on Dingly Dell.

"My main worry is that I've changed so much physically and environmentally in the past two years that I haven't had a settled place to sit down and write. When I lived in Gateshead I was on the dole for a year and I wrote fifty songs including 'Lady Eleanor' and 'Winter Song' and 'Fog On The Tyne' - they were all written during that period and it seemed to be a very atmospheric house. I want to recapture that thing where I can sit down and relax and write."But he continued to live in a stone conflict. He and his family lived in Barnet for several years - a lot longer than they would have liked - and only recently returned to Newcastle. There was this period of change but it represented a sequence of negatives and was totally unstimulating. The summer of '72 was a worrying one for Hully. 'Fog On The Tyne' had gone top of the charts, and Nicely Out Of Tune, anachronistically, was just beginning to break. Hully knew that the latter had been far stronger poetically and the follow up hadn't matched up - but he gave a vote of confidence in Bob Johnston.

"He offers us a great atmosphere to work in and ideas on the selection of material," he said at the time. Alan concluded that interview in May '72 by stating that the band wouldn't outlive its purpose. "I think Lindisfarne's relationship will grow - never out, it'll just sprout," he quipped enigmatically. When the band did sprout it seemed to be purely from convenience and with very little design. By July Dingly Dell was complete although at the time, Hully, carried away by the heady excitement of a new release claimed that the album would remain untitled "because the music says it all". He was enthusing about the "dirty, raunchy American sound" that Bob Johnston had manufactured and I could never quite reconcile this with the original concept of the band. I felt that if the songs were good enough then this would be a bad thing, but if the songs were below par then it could be the saviour of the album.

"It's the music that counts," exclaimed Alan and seemed delighted that the standard of playing and arrangement had reached a new level of sophistication. When the album came out in September, sure enough it was packaged in a plain brown sleeve although by this time Dingly Dell, the seven minute closing track had been picked out for the title. With this song, clearly the highlight of the album, Ray Laidlaw's brother Paul set a new precedent by orchestrating it whilst Alan and Rod are the only two band members featured. My reaction on hearing it was the same as when I first heard Poco orchestrated on the equally memorable 'Crazy Eyes'. Yet oddly, 'Dingly Dell' had almost found its way onto Fog On The Tyne and had been written years before at a time when Alan was writing all his best songs, inspired by the philosophical writer he happened to be immersed in at that particular time. So Cowe's 'Go Back' was another old song that had resurfaced - this time inspired by reading R D Laing.

The much advertised Rod Clements song wasn't so special after all, and apart from a few instrumental fillers

the best song was Alan's beautiful 'Wake Up Little Sister' - a piece of pure whimsical tenderness that was rightly to become a stage favourite. But the air of mild rebellion on 'Bring Down The Government' and the lament 'Poor Old Ireland', although atmospheric from the concert platform, were sentimentally weak from the twelve inches of plastic on which they were cut. Alan Hull was really beginning to sound like a man who had nothing to say. I don't think anyone seriously thought that Lindisfarne would challenge the Stones despite their newly contrived musical virtuosity. It wasn't that the band improved musically to any great degree, simply that they had never really needed to think too heavily about arrangements and sound quality before - not as long as Hully had acoustic, electric guitars and keyboard instruments on stage, Jacka his harp and mandolin, Si on banjo, mandolin and guitar, Rod on fiddle and bass. Rod used to scrape out some dire fiddle parts but in the general melee Lindisfarne always cranked out a fulsome happy backing on which the voices were overlaid. The anachronism persisted.

The much advertised Rod Clements song wasn't so special after all, and apart from a few instrumental fillers

the best song was Alan's beautiful 'Wake Up Little Sister' - a piece of pure whimsical tenderness that was rightly to become a stage favourite. But the air of mild rebellion on 'Bring Down The Government' and the lament 'Poor Old Ireland', although atmospheric from the concert platform, were sentimentally weak from the twelve inches of plastic on which they were cut. Alan Hull was really beginning to sound like a man who had nothing to say. I don't think anyone seriously thought that Lindisfarne would challenge the Stones despite their newly contrived musical virtuosity. It wasn't that the band improved musically to any great degree, simply that they had never really needed to think too heavily about arrangements and sound quality before - not as long as Hully had acoustic, electric guitars and keyboard instruments on stage, Jacka his harp and mandolin, Si on banjo, mandolin and guitar, Rod on fiddle and bass. Rod used to scrape out some dire fiddle parts but in the general melee Lindisfarne always cranked out a fulsome happy backing on which the voices were overlaid. The anachronism persisted.

Lindisfarne toured in the autumn of

1972 with Genesis and Rab Noakes/Robin McKidd, still winning hordes of new followers and therefore drawing attention to Nicely Out Of Tune which still harboured some of the more requested numbers. It was a success based on the brilliant writing of a musician who happened to be undergoing a long period of mental conflict back in the mid-sixties. A man who variously lived on the breadline, worked with mental patients, read some of the heaviest literature around, and fell in love and got married at the same time. If that isn't the kind of conflicting environment that breeds good songs . . . small wonder that the ensuing routine of a touring rock band on the road proved to be anti-climactic. "The folk feel wore a bit thin because we couldn't get through to the audience," Ray Jackson had said. And as the band played larger venues it was obvious the sound would have to swell by some degree - particularly if Lindisfarne were to enjoy any success in the States. For they clearly felt that this had counted against them first time around

In the August Lindisfarne laid all their new songs on the unsuspecting thousands at the

Crystal Palace Garden Party, previewing them for the first time. It seemed to pay off and thus the band went off on tour the next month highly confident, winding up at Newcastle City Hall at the end of September - just nine months after their Christmas show. I recall fondly that particular visit to Newcastle for it provided the basis of an entire background piece to the formation of Lindisfarne, so that the concert became of secondary importance. The presence of Dave Wood and Joe Robertson, who had managed the band prior to Tony Stratton-Smith, Barbara Hayes, who had formed Hazy Music publishing with Alan Hull, and people like Jeff Sadler, who had worked with the band until they came to London to hit the big time, coupled with the willingness of these people to talk about the past, provided a weekend of pleasant nostalgia and some fine copy which covered the centre page spread of Sounds (7/10/72).

In the August Lindisfarne laid all their new songs on the unsuspecting thousands at the

Crystal Palace Garden Party, previewing them for the first time. It seemed to pay off and thus the band went off on tour the next month highly confident, winding up at Newcastle City Hall at the end of September - just nine months after their Christmas show. I recall fondly that particular visit to Newcastle for it provided the basis of an entire background piece to the formation of Lindisfarne, so that the concert became of secondary importance. The presence of Dave Wood and Joe Robertson, who had managed the band prior to Tony Stratton-Smith, Barbara Hayes, who had formed Hazy Music publishing with Alan Hull, and people like Jeff Sadler, who had worked with the band until they came to London to hit the big time, coupled with the willingness of these people to talk about the past, provided a weekend of pleasant nostalgia and some fine copy which covered the centre page spread of Sounds (7/10/72).

There seems little point in hauling any of that back to the surface since most of it predates Lindisfarne and this story is specifically about the rise and decline of that band after they came to London. But one quote from Dave Wood, who recorded and stored Alan's songs at Impulse studios, is particularly significant. "I have tapes of about 280 Alan Hull songs, all of which you could get the group to do now. I find it hard to come across a song I don't like. Alan was always a little ahead of his time and he changed my way of thinking completely - some of his songs like 'Schizoid Revolution' were frightening."

I have a lot of memories of that particular visit to Newcastle not least of them being Alan Hull's mum, oblivious to the occasion, storming into the Haymarket, protesting that Alan hadn't been home for his tea.Late that autumn the band returned to the States and clearly a lot was going wrong. They had become stale and they weren't taking off at all in the States. Rumours started spreading that the band would split . . . that they had already effectively split, that Hully would go solo. Rumours gathered strength when it was announced that Alan would start recording a solo album in March 1973.

In the States Lindisfarne toured with The Kinks. I was in New York at the time and by sheer coincidence checked into the room adjoining Tony Stratton-Smith's in the Gorham Hotel. He suggested a train journey to Washington next day and thus we set off eagerly in the early morning. At the hotel in Georgetown there was nothing to be seen of the group . . . and we eventually located them in a bar called Mr Smith's, slumped behind four empty bottles of Chateauneuf Du Pape.

The gig was an embarrassment - a near disaster saved only by Jacka's cheekiness and final ten-minute harmonica medley (what a way to save a show). That night it all fell into perspective. Kinks headlining, Ray Davies's controlled buffoonery, evoking so much laughter with his 'Demon Alcohol' sketch whilst Lindisfarne scarcely won a murmur of sympathy. Both bands are looners, both have so many good songs and yet on the night Lindisfarne looked Division IV and The Kinks Division I. Lindisfarne, without a shred of concern for the audience, and a total lack of professionalism, were a shambles. And just as a man resorts to his mother tongue with drink, so Jacka had pulled out a Geordie accent which was so thick and rife with idiosyncrasies that they probably wouldn't have known what he was talking about in Middlesborough!

After America came Australia and Japan and Lindisfarne returned with their tails between their legs. The band decided on a temporary split whilst Hully recorded a solo album, and he sent up to Dave Wood for a whole bunch of his early demos to form the basis of his new album. He candidly admitted that he hadn't been writing of late and it was as though he'd been saving a bunch of songs pre-dating 'Lady Eleanor' and 'We Can Swing Together' until such time as he was ready to record solo.

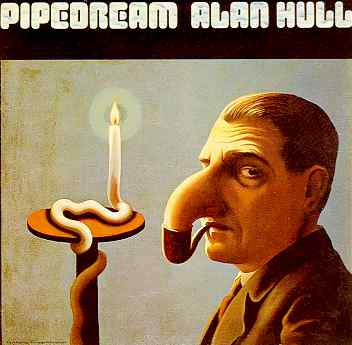

The sessions started on March 17 and Alan used an all Geordie line up including Kenny Craddock, Ray Jackson, Ray Laidlaw, John Turnbull and Colin Gibson, shipping in vast crates of Guinness and tequila daily. In fact had Glencoe not looked to be on the threshold of something mighty it is highly likely that Jon Turnbull would have joined Lindisfarne when the split finally came. "There'll always be a Lindisfarne. I'll be doing some solo things but they won't be of great importance - it's much better to be playing with a band," proclaimed Alan before the decision was made. He announced that the band would relaunch with a new vigour in May, but three weeks later Alan confirmed that he would be leaving the band. It should be emphasised at this point that Alan Hull's Pipedream album had been a huge credibility restorer - an album that I played constantly and placed alongside Nicely Out Of Tune as containing the best songs he had ever written.

Typically Hull took a surrealistic Magritte painting as an album cover to help illustrate the theme of his music. About fifty percent of the songs were old and the remainder he had written specifically for the album.; it's not hard to tell which is which although the album hits an immediate peak and retains it throughout. The album was still waiting its release when Hully decided to go solo. Now there's a lot of difference, in the eyes of the public, between a man leaving to go solo and a direct split right down the middle of a band. Thus it happened that two fifths of the band decided to break away when Jack realised that his sympathies extended more towards Alan Hull than the rest of the band; somehow fitting when you recall that the original nucleus of Brethren was Ray Laidlaw, Rod Clements and Si Cowe - Jacka and Hully joined later.

Hully badly wanted a new band because the Trident sessions for Pipedream had charged him with renewed enthusiasm. He already had some songs left over and was writing prolifically. But it took a long time to get the new band together. But it took him a long time to get the new band together and they went on tour in the summer and played at the Reading Festival at the end of it all. The new band comprised Charlie Harcourt who had returned from a fairly unsuccessful stint on the west coast of America with Cat Mother; Tommy Duffy who'd never been happy since the Arc/bell & Arc set up, and had subsequently done some time with Gary Wright's Wonderwheel; then there was Paul Nichols from a promising band called Sandgate on drums.

Before the end of 1973 the band's first album Roll On Ruby was released by Charisma, thus marking the end of Alan Hull's successful but often stormy association with the company. Alan specifically wanted a six-piece band and he, Jacka and Kenny Craddock took time to piece the band together. But by the time they went out on tour they were beating out some tasty licks and had some fine songs. I always liked Tommy's contribution to the album Arc . . . At This, and Charlie had penned a couple of good things for a Jackson heights album called King Progress. Kenny Craddock was an established and prolific writer but would there be room for four writers to get their rocks off in a single band?

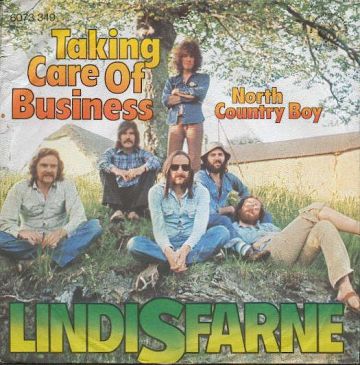

Ultimately there was not but initially Lindisfarne came out with a well-balanced album - four Alan Hull songs, all gems, three from the Kenny Craddock/Colin Gibson partnership in a sort of stompalong goodtime vein more reminiscent of the old Lindisfarne. In point of fact the exception was 'Roll On River' which was more reflective. Tommy Duffy had three songs highlighted by 'North Country Boy' whilst the other two tended to fall in the shadow of Alan Hull's better songs. The decline set in during 1974. Lindisfarne wound up with a new recording contract (Warner Bros) and management (Tony Demetriades) but although they continued to knock out some tasty music, their career was obviously going nowhere.

Ultimately there was not but initially Lindisfarne came out with a well-balanced album - four Alan Hull songs, all gems, three from the Kenny Craddock/Colin Gibson partnership in a sort of stompalong goodtime vein more reminiscent of the old Lindisfarne. In point of fact the exception was 'Roll On River' which was more reflective. Tommy Duffy had three songs highlighted by 'North Country Boy' whilst the other two tended to fall in the shadow of Alan Hull's better songs. The decline set in during 1974. Lindisfarne wound up with a new recording contract (Warner Bros) and management (Tony Demetriades) but although they continued to knock out some tasty music, their career was obviously going nowhere.

Miraculously that six-piece line-up remained together throughout 1974 and at the end of the year released Happy Daze, produced by Eddie Offord, it was released but largely dismissed by the pop press. Lindisfarne were written off as has-beens but maybe it was fortunate that the whole incident was overshadowed by the much pre-publicised film debut of Alan Hull in Squire which sensibly, was a fairly unambitious debut which deserved its fine reviews. All Hully had to do was act normal for half an hour, as somebody put it, and certainly the profile of a working class reject, on the dole, living out the fantasy life of a country squire and then ultimate suicide, did seem to ring a few old familiar bells.

At the beginning of this year Lindisfarne split. Happy daze was a tepid album to go out under the name Lindisfarne but it never merited the severe criticism it received. Yet a complete split by this time had become inevitable and I doubt whether press reviews could have affected the eventual outcome in any event.

Jerry Gilbert 1975