|

| by Caroline Boucher |

| from Music & Disco Echo, Feb 2nd, 1972 - discovered by Michael Clayton |

|

|

|

| by Caroline Boucher |

| from Music & Disco Echo, Feb 2nd, 1972 - discovered by Michael Clayton |

|

|

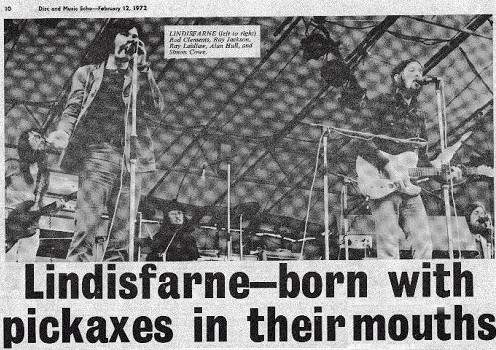

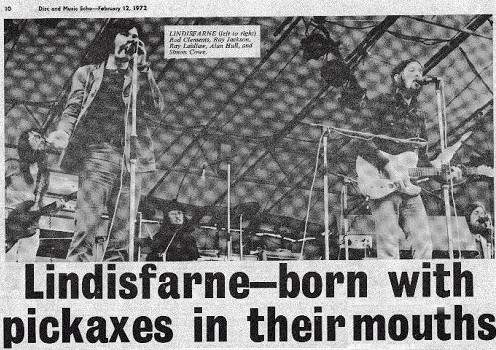

It is meet and right that our Brightest Hope award this year should go to Lindisfarne, the most sincere, straightforward and no-nonsense band to emerge out of 1971.

They made the final rung of the ladder to success in the latter half of that year with Fog On The Tyne and the few months leading up to it, but all through the early part of the year their name cropped up here and there, whisper whisper, so you were quite well aware of them creeping up behind your shoulder.

And from the very early days Lindisfarne stood out because of their distinctive songs - polished Northern pub-folk songs. And they were fiercely proud of their Newcastle roots, they didn't flounder and wallow in the nostalgia of back-home as a lot of Liverpool musicians seem to do, they were just very Geordie. As Alan Hull said to me when I interviewed him last November:

“The kids in Newcastle have given us their support because we've come down to London and shit on a lot groups that were born with silver spoons in their mouths. We were born with pickaxes in ours and we spat them right out at them."Lindisfarne began ten years ago when Ray Laidlaw got a drum kit from his grandfather for his 13th birthday. Guitarist Simon Cowe lived down the road and they formed a group called the Aristokats which lasted for about two years. Rod Clements (bass and violin) was at school with Simon and then Ray met Ray Jackson (mandolin, harmonica, vocals) at Art College. Alan Hull had been playing with other Newcastle groups all this time and they asked him to join them. The first gig wasn't very successful together, they gave it another go a few months later and late in 1969 the current line-up of Lindisfarne was on the road, known as the Bretheren.

Their first album Nicely Out Of Tune (so called because they always seemed to do just that playing in sweaty little clubs) sold as well as most first albums, perhaps a little better than some. In between that and the second album, Fog On The Tyne, they began to build up a following. Bob Johnston was brought in to produce it and that made a few people sit up and think. The result made almost everybody sit up and think, because that made Lindisfarne. It outsold the first album in a matter of weeks and was rated by many as the album of 1971.

Their manager is Tony Stratton-Smith who managed the Nice, and also has Van der Graaf Generator and Genesis under his wing. He first heard tapes of Lindisfarne in 1970 and found something haunting about the music although everybody else in the office loathed them, but he went ahead and signed them.

"When we first heard Lindisfarne the most important thing was the songs, I thought they really shone. I signed them on the strength of them, and then after that the next thing that convinced me we had an outstanding band was their rare ability to get it on with an audience very quickly."

Certainly he's a happy manager. In March Lindisfarne do their first tour of America opening at Carnegie Hall with the Kinks. In May they tour Europe, during the summer they record their next album and possibly return to America and in September they do a national tour here.

One Only hopes that they manage to keep their isolated identity throughout all this hustle and bustle. Their songs so plaintively reflect the North, the whistle-down-the-wind solitariness of the island they called themselves after.

Lindisfarne ought to be sent back to Newcastle for compulsory refresher courses to keep their music so good, honest and true.