|

|

||||

|

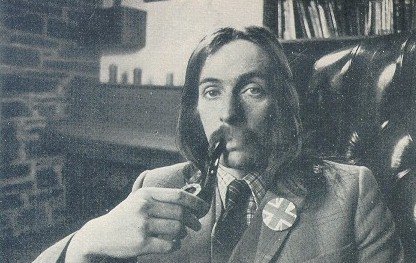

Portrait taken in 1975 courtesy Elsa Dorfman.

Check out her website on: |

SQUIRE : on television

"Alfy is 30 and on the dole. So what does he want with a stuffed tern, a shooting stick, a Harris tweed suit and a shotgun?"

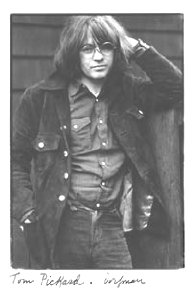

This was how the Radio Times announced 'SQUIRE', the first television play written by Tom Pickard which made its screen debut on BBC2 at 10.15pm on the evening of Monday 25th November 1974, one of the new 30 minute plays commissioned as part of their innovative 'Second City Firsts' series.

Newcastle born writer Tom Pickard made his name during the early sixties as one of the emerging band of British 'underground' poets, inspired by the beat poetry coming out of America led by Kerouac and Ginsberg. Befriended by the influential figure of Basil Bunting, Tom ran a performing arts club known as the Morden Tower in a back alley close to the city centre, where local artists of all kinds would hang out - amongst them the painter Richard Hamilton, singer Bryan Ferry and songwriter Alan Hull. According to Tom, Hully made his performing debut at the Tower.

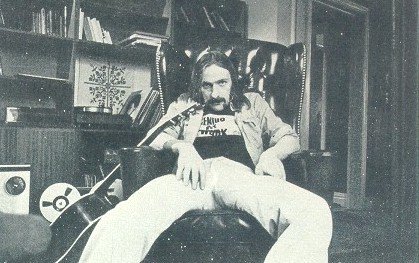

The pair remained firm friends and when the Second City Firsts commission came about, Tom not only asked Alan to write the incidental music but cast him in the lead role of Alfy, a 30 year old dole-ite with delusions of grandeur. It was Alan Hull's first acting role, but he carried it off with some aplomb, causing the

Daily Telegraph to state - "He could be the first pop singer since Adam Faith to make a successful transition to

acting."

Martin Jackson of the Daily Mail agreed, saying "it looks like the beginning of a new acting career, for Alan Hull is also working with the production team - writer Tom Pickard and director Barry Hanson - on a television version of Dostoievsky's 'The Idiot', transformed to Tyneside and likely to be retitled The

Nutter."

Writing in the Daily Telegraph, Sean Day-Lewis commented -

"Second City Firsts was given a splendidly rejuvenating injection of new life by moving from the Midlands to the North East and harnessing two of Newcastle's brightest and most unruly talents. Tom Pickard's Squire said little, but said it in such a lively way that 30 minutes seemed far too

short."

The Daily Mail suggested that "Hull was at ease in the role, extracting a little sour relish from showing the lack of true opportunities for a secondary modern school graduate unlucky enough to be both naturally indolent and resident in an area of chronic

unemployment."

Not all of the newspaper reviews were so kind; the Daily Mail concluded that

"New Realism in drama has been around for long enough now to become as cliched as the style it ousted - and that element worked against Pickard's

play."

In his excellent Lindisfarne biography, Dave Ian Hill quotes Alan's own version of events - "Tom - a great poet, great Socialist, great friend - rang me up and said "I've got this play, for BBC2, do you want to write the music for it?". "Be proud to" I said, "Give me the script, come round and we'll talk about it". Alan then discovered that Pickard also wanted him in the lead role. "So I said, I can't act". So he says "Can you read?" "I dunno, just about". So he says, "Well, you can act". So I got the job!"

|

The play itself centres around Alfy, a charming workshy layabout who keeps his wife and two kids courtesy of the dole office, yet at the same time pictures himself as a country gentleman. Alfy's wife Mary is played by Madelaine Newton, the architypal hard-done-by housewife who struggles to feed, dress and pack the kids off to school, while her husband lies daydreaming in bed. When he eventually rises, Mary scolds: "You haven't even shaved yet" to which Alfy replies: "I'm only signing on, y'knaw, not bloody kissin' arses." Most of the female Lindisfarne fans will recall their first sight of Hully's bare backside, as in one scene a stark naked Alfy runs down the narrow staircase of his terraced home! The pressure of poverty constantly keeps husband and wife at loggerheads, yet Alfy always has time for his kids; when Mary shouts at them not to forget their dinner money, Alfy gently tells them not to waste it - "no more Tizers and Crunchies". |

The two children in the play are played by Catherine and Matthew

Pickard [see pic].

When he finally arrives at the dole office, Alfy is sweetness itself to the girl behind the counter, responding to every question with a chat-up line or a joke -

Girl: "Did you pass any exams or get any qualifications?"

Alfy: "Just for swimming"

Girl: "I haven't got any vacancies for ducks."

When the reality of his situation gives way to a fantasy life, Alfy starts to frequent a local

auction room sale, where his dole money is frittered away - on the stuffed tern, the shotgun and shooting stick! Director Barry Hanson cuts between the grimy terraces of the Newcastle streets with the obligatory shots of the river and Tyne Bridge, to some dream sequences where Alfy plays croquet with his children, on the lawn in front of his imaginary country mansion. Back in the real world, the bailiffs are a constant threat, coming around at all hours to try and repossess the furniture, with Mary often left alone to keep them at bay. When told that they'll be back, she barks "You'll not get through the door" - the bailiff simply sneers "Ah, but the law allows us to kick it in, pet." Alfy arrives home one day to witness the inevitable, as a van leaves with their furniture, and a taxi pulls up to take Mary to her mothers "Come and see the bairns when you want, but don't ask me to come back" she tells him. At this point the soundtrack features a snippet of Tom's 'Persecution Complex' that includes the ominous lines:

"peeling mashed potatoes,

when your wrists are slashed"

Sharply dragged back to reality by Mary's leaving proves to be the final straw; life has simply become too much for Alfy to bear and he makes a suicidal leap from one of the Tyne bridges into the murky river water below. There are elements of both Tom and Alan's early life within the play; both would have come up against the quandary of doggedly following their chosen professions in the arts while trying to support a young family. But whereas Pickard and Hull had the talent to succeed, Alfy and thousands like him, were, and still are, not so lucky.

I asked the author of the play, Tom Pickard, for his memories of 'Squire'

Chris Groom The Chicago Review published 'A Work Conchy', (as in conscientious objector) part of a larger work of yours titled 'Rough Music (Ruff Muzhik)', which mentions a fascinating place - The Morden Tower. Can you tell us a bit more about the Tower, is this where you first met Alan and can you confirm that this is where he made his first public performance?

Tom Pickard The most detailed information on the Morden Tower at that time (the decade from 1963-73) is on the Chicago Review website

(humanities.uchicago.edu/orgs/review/461/461homepage.html). It was rented and run as a poetry reading/arts centre on no money by Connie Pickard and myself.

Basically it is a medieval tower on the city walls of Newcastle situated in Back Stowell Street along a stretch of the wall that runs between Westgate and Gallowgate.

A sense of real history, in a ditch, or a narrow alley that factories and warehouses backed onto. Nowadays China Town backs onto it, and, just as those factories used to pump out noxious fumes the restaurants garbage sometimes spills onto the cobbles.

It was and may still be used by prostitutes who'd take their clients up against the 12th century wall, and by couples and people seeking dark unfrequented places with two exits, and by drinkers to empty their bladders. The walls are very high and thick. So, like city walls everywhere and throughout time, Back Sowell Street has had continuous use as a fuckpit. Think of Shamhat in Gilgamesh, the oldest extant written story (2500BC, and old even then), where she plies her trade as a hierodule, not in the temple, but against the walls of Uruk before she is hired to use her erotic skills to civilise Enkidu, the wild man who runs with the beasts in the forests. What better introduction to civilisation, and at the very boundary walls of the city. We wanted to run a bookshop along the lines of Jim Hayne's Paperback Bookshop, in Edinburgh, where wild and avant guard books were on sale and where there was a sense of otherness. Haynes also co-sponsored the Edinburgh festival's Writers Conference (1963) where William Burroughs amongst others made his first British appearance. Anyway, the Morden Tower was a near derelict place, the cheapest we could find to rent in the city, and where a rep for a publisher told us we'd be better off breeding pigeons than trying to run a bookshop. As we had no capital to set up a fully stocked bookshop, the place became an international poetry centre where some of the most interesting poets in the world came to perform, attracted by the presence of the lost elder, Basil Bunting. In those days most of the poets coming to the tower were outside of any perceived establishment, and there was a tension between the arts authorities (City Council/Northern Arts) and us as they continually tried to close the place down, one way or another.

I don't remember if it's the first place that I met Alan, but we did get him to play there, and he did tell me later that it was his first public performance. Pat would know for sure. Alan was one of the talented musicians around the town, and we drank in the same pubs and clubs. The tower, for a number of people in the town, was an acceptable place to visit, perhaps because of its ill-reputed location and ill-reputed activities. A good friend, Barry Scaum, took me to a pub/club on the quayside, to hear Alan sing and perhaps it was after that we got him on at the tower. Or maybe the other way round. The order of events is confused, I just know what Alan told me.

Was Squire a direct commission from the BBC or did it already exist in some form?

The Squire was a short story before it became a script. I was contacted by Barry Hanson, the director of Squire, when he was David Rose's assistant at the BBC in Birmingham. They were running an innovative tv drama series with a non metropolitan emphasis called Second City Firsts. They were looking to encourage new writers, and I was one of them. Barry wrote asking if had anything suitable and I sent him the story and he commissioned me to turn it into a script. Barry Hanson, a Bradford boy, had been a student at Kings College (when Newcastle University was an outpost of Durham University), doing English, and he used to come to the Morden Tower readings. He had also organised at least one of the first Student/City Arts Festivals in co-operation with the City Council. Later he worked at the Royal Court Theatre, and went on to produce The Naked Civil Servant, Gangsters, and The Long Good Friday, amongst much else. David Rose became commissioning editor at Channel 4 for Film On Four for a few notable years.

Was it your idea to cast Alan as Alfy in the lead role and were you involved during the filming? I see that your two children also appear as the kids in the play.

Yes, it was my idea to cast Alan. By then Lindisfarne had become famous and I think Alan was still living in London. He had a kind of sulky insolence that came across on stage that I thought would suit the role. I was also proud of the band, a fan, being a committed supporter of local genius. And I wanted the film to have that kind of music to give it a root and a raunch that was tangibly Tyneside.

I suppose there was some disapproval of musicians being actors or poets being script writers, but the series Second City Firsts was designed to encourage such experiments.

I wasn't allowed to be involved in the filming as we were going through a volatile breakdown in my marriage. My two children were in Squire as I wanted their mother to get a few quid out of it, and I wanted to be able to see them years later as they were as children. They were also there because much of Squire was written out of my life, and picked at the flaw in my own yearnings and fragile self-belief. Alfie was someone I could have been and sometimes was. You don't ask about the street and house where it was set. That brick street of blackened workers houses that overlooked the dark river Tyne had been my home. In fact it was the first place I'd had on my own (I was 27), ever. As soon as I left my parent's home (aged 16) I moved in with my lover who became my wife, and we'd trailed over many years from friend's house to house before getting a place after which the marriage broke up. The film was shot in Hubert Terrace, (now demolished) and was the flat I was able to rent after the split up. The street, the flat, the state of mind, featured in my poem Hero

Dust.

"this street is built with bricks

of furrowed brows

whole gutters explode

and tremble with sparrows"

It was an important location on my map. Barry thought, given the volatile nature of the break-up, that the film stood a better chance of being made if I wasn't there. I resented it at the time because I wanted to learn about directing and maybe do some.

You should also mention the bailiffs. They were always around and had once, in pursuit of a debt owed to Newcastle City Council, cleared an attic office I rented at the bottom of Westgate Road of its meagre contents: a two bar electric fire, a table, a chair and a typewriter.

What was your opinion of Alan's performance and were you happy with the final product?

I thought Alan's performance good. He pretty much played himself. He was sometimes a squire, I was sometimes Alfie. He could play a good scruff. I enjoyed the film, but cringed a bit with the dialogue in the dole-office scene with Madeline Newton that I thought over-written, although it was more or less the verbatim conversation I'd had in one of the more understanding and surreal dole offices that have underwritten my career. It used to be an old three or four story Victorian municipal building that stood on Windmill Hill overlooking the Tyne, as much of Squire does. It also occurs in another poem written in Gateshead a few years earlier, The Devil's Destroying Angel Exploded, or Coal Hewers In An

Uproar "moon full above the dole."

Is it fair to say there is a similarity to your own early situation (and Alans for that matter) in the play?

As I've said, most of the story was taken from my own life. I'm not sure about Alan's early experience as I think he worked rather than spent a lot of time on the dole. As a working-class bloke with no qualifications (I failed the 11 plus and that was the peak of my academic career) and with no skills other than a developed and developing ear for the music of poetry, and with children, I had no choice but the dole. What I could earn from labouring was less than the state thought minimal for a family's survival. Also there weren't many jobs about that you could give that name to. Initially it may have been different for Alan, as a working-class bloke with no dependents, it would have been worth his while 'working'.

Is it true that you and Alan were working on a Tyneside version of 'The Idiot' to be renamed 'The Nutter' - and did anything ever come of it?

I'd just read Dostoyesky's 'The Idiot' and when the Squire was being previewed we were interviewed by a pleasant woman, a famous film critic working for the Times, or the Observer, and as a quip threw in the idea of a Geordie version and calling it The Nutta! We enjoyed the joke and let it ride. Although we did often discuss other collaborations, including that one nothing came of it.

Do you know if Alan already had all the songs that appeared on the album - I assume that only a couple and some incidental music were used in the play itself.

He wrote the song, 'Call Me The Squire' for the programme and may have used other stuff already written (for instance Fog On The Tyne). He also performed a verse of my song 'Persecution Complex (Call me Percy for short)' and never paid me the royalty he got for it!

Finally, did you work with Alan again on any other project - I believe you were on the bill for the Swan Hunter benefit a few years back.

We toyed with various ideas, but mostly I wanted to write some lyrics and he wanted to write the script/book so nothing usually came of it. I composed the back cover (sleevenotes) for his album and brought him into Jarrow March. This was a one hour BBC Radio 3 feature that I'd been commissioned to make, for which he wrote 'Marshall Riley's Army' after a long, late night conversation down the phone when I was just back from the pub and blasted and giving him all the details. The scratch pad at the other end was audible.

© Tom Pickard

My thanks to the inimitable Tom Pickard for taking the time and trouble and for delving back 27 years into the memory banks; to Elsa Dorfman for the use of her photography and to Julia Revell for keeping those invaluable press cuttings!

Chris Groom